Meeting with Aldous Huxley

If you go to Lancaster at the edge of the Mohave Desert

you will be close to Pearblossom Heights, which is close to

Llano, where the Huxleys lived. Hitchiking and walking it

took me almost until noon to reach their place set back

from the road and surrounded by trees and shrubs, like a

kind of oasis in that hot, dry climate.

If you go to Lancaster at the edge of the Mohave Desert

you will be close to Pearblossom Heights, which is close to

Llano, where the Huxleys lived. Hitchiking and walking it

took me almost until noon to reach their place set back

from the road and surrounded by trees and shrubs, like a

kind of oasis in that hot, dry climate.

Mr. Huxley came out to greet me in the front garden. A very

tall, handsome man, it was obvious that he suffered from

visual impairment. He was followed by his wife, Maria, a

lovely Belgian lady who, upon seeing my underweight frame,

said briskly: "I'm going to fatten you up!" So, after the

usual small talk of introducing myself and being

introduced to them, I was invited to lunch, and we soon sat

down. As I did so, I noticed a large sculpture of D. H.

Lawrence in the corner of the garden.

Mr. Huxley came out to greet me in the front garden. A very

tall, handsome man, it was obvious that he suffered from

visual impairment. He was followed by his wife, Maria, a

lovely Belgian lady who, upon seeing my underweight frame,

said briskly: "I'm going to fatten you up!" So, after the

usual small talk of introducing myself and being

introduced to them, I was invited to lunch, and we soon sat

down. As I did so, I noticed a large sculpture of D. H.

Lawrence in the corner of the garden.

They wanted to know a little of my recent history, and

so I described my meeting with Krishnaji, and the

quality of immense silence that I felt about his person.

Huxley said: "Well, you see, Krishnaji took you right

into the radiant silence wherein he

himself dwells. So you didn't have to wait in the

anteroom." I spoke about the great difference between

him and a man named Peter the Hermit who I had met on my

journey to Ojai. He lived in a kind of "camp" in a tent

with two dogs, one of whom was named "Annie Besant."

Later I found out that Peter had been a radical organizer

with the American I.W.W., often hopping on trains to get

around the country. On one of his stops he went to

a public library where, quite by chance, he found a

book by Brother Lawrence called The

Practice of the

Presence of God. And this book, in an instant, converted

him from radical political life to radical spiritual

involvement. When I met him he was in his sixties, all

dressed in white, with a clean, scrubbed look about

him. He mentioned his sparse vegetarian diet and his

shunning of all types of addiction.

They wanted to know a little of my recent history, and

so I described my meeting with Krishnaji, and the

quality of immense silence that I felt about his person.

Huxley said: "Well, you see, Krishnaji took you right

into the radiant silence wherein he

himself dwells. So you didn't have to wait in the

anteroom." I spoke about the great difference between

him and a man named Peter the Hermit who I had met on my

journey to Ojai. He lived in a kind of "camp" in a tent

with two dogs, one of whom was named "Annie Besant."

Later I found out that Peter had been a radical organizer

with the American I.W.W., often hopping on trains to get

around the country. On one of his stops he went to

a public library where, quite by chance, he found a

book by Brother Lawrence called The

Practice of the

Presence of God. And this book, in an instant, converted

him from radical political life to radical spiritual

involvement. When I met him he was in his sixties, all

dressed in white, with a clean, scrubbed look about

him. He mentioned his sparse vegetarian diet and his

shunning of all types of addiction.

Smelling my odor of tobacco he quickly fixed me with a

glaring eye and started in: "Yes, I can see that,

although you talk about spiritual life, that you're just

like the rest of them, standing in line for those

doomful cigarettes, shambling around life like an

animal, without the slightest notion of what you

ought to be doing.

Smelling my odor of tobacco he quickly fixed me with a

glaring eye and started in: "Yes, I can see that,

although you talk about spiritual life, that you're just

like the rest of them, standing in line for those

doomful cigarettes, shambling around life like an

animal, without the slightest notion of what you

ought to be doing.

Then he shouted: "WHEN ARE YOU GOING TO GET UP ON YOUR

HIND LEGS AND AT LEAST ACT LIKE A MAN?" As I recounted

all of this to the Huxleys they laughed heartily. And Mr.

Huxley commented: You must understand, Kerwin, if you as a

young man go about contacting people who are on the

spiritual path, rest assured that they are going to

notice a great deal about you, and perhaps (without any tact)

make direct comments about what they see!" So I continued

about Peter the Hermit, and his own declaration of

independence from middle class life: He had said: "I wash

my own (pointing to his clothes), and I clean and prepare

my own food of the simplest kind."

Then he shouted: "WHEN ARE YOU GOING TO GET UP ON YOUR

HIND LEGS AND AT LEAST ACT LIKE A MAN?" As I recounted

all of this to the Huxleys they laughed heartily. And Mr.

Huxley commented: You must understand, Kerwin, if you as a

young man go about contacting people who are on the

spiritual path, rest assured that they are going to

notice a great deal about you, and perhaps (without any tact)

make direct comments about what they see!" So I continued

about Peter the Hermit, and his own declaration of

independence from middle class life: He had said: "I wash

my own (pointing to his clothes), and I clean and prepare

my own food of the simplest kind."

I commented: "But why does he have to live in a kind of

gypsy camp on the edge of town?"

I commented: "But why does he have to live in a kind of

gypsy camp on the edge of town?"

"Well," said Mrs.

Huxley, "it may be a way of showing the

world (and you too) that he is a beginning renunciate

who has embarked on a spiritual life which is bare and

simple without any of the amenities which are common in

modern America."

"Well," said Mrs.

Huxley, "it may be a way of showing the

world (and you too) that he is a beginning renunciate

who has embarked on a spiritual life which is bare and

simple without any of the amenities which are common in

modern America."

"Yes," said Mr. Huxley,"in a country like this, which is

based mainly upon consolations, the person who rejects that

ideal will probably live unconsoled and perhaps adhere

to a radical regime of fasting and prayer -- at least

in the beginning stages."

"Yes," said Mr. Huxley,"in a country like this, which is

based mainly upon consolations, the person who rejects that

ideal will probably live unconsoled and perhaps adhere

to a radical regime of fasting and prayer -- at least

in the beginning stages."

I said: "Well, I have heard of communities where people

practice a simple form of Communism, where they work

together and share everything, but I have also heard that

these communities rarely last --"

I said: "Well, I have heard of communities where people

practice a simple form of Communism, where they work

together and share everything, but I have also heard that

these communities rarely last --"

"Quite so," interjected, Mr. Huxley, "and indeed right

across the road from us is a powerful example of

one such experiment. May I tell you about it?"

"Quite so," interjected, Mr. Huxley, "and indeed right

across the road from us is a powerful example of

one such experiment. May I tell you about it?"

"Please do," I said.

"Please do," I said.

He continued: "In the early part of this century a large

group of people (who were idealists) gathered together and

formed a community known as Llano, right across the road

in the same area which we live now. They had been inspired

by the Christian Gospels and by various other groups

who had decided to do something radically different in

regard to living together so that like "The Three Musketeers"

it was 'All for one and one for all!' That was the

ideal, anyway."

He continued: "In the early part of this century a large

group of people (who were idealists) gathered together and

formed a community known as Llano, right across the road

in the same area which we live now. They had been inspired

by the Christian Gospels and by various other groups

who had decided to do something radically different in

regard to living together so that like "The Three Musketeers"

it was 'All for one and one for all!' That was the

ideal, anyway."

"How many were involved?" I asked?

"How many were involved?" I asked?

"Oh," he answered, "At first there was a small core

group of planners and movers and shakers, and then a large

group of interested, but not really active people. All in

all, several hundred, I believe.

"Oh," he answered, "At first there was a small core

group of planners and movers and shakers, and then a large

group of interested, but not really active people. All in

all, several hundred, I believe.

"But how long did it last?," I said.

"But how long did it last?," I said.

Huxley pondered awhile,

and then answered: "They had

about 300 acres, enough capital and enough

equipment and idealists to last up until about 1925.

Then the intense conflict between idealism and actuality

began to cut into their hopes. And so they got to

fighting, and within a few years the whole thing just

fell to bits, and what is left of the wreckage across

the road is all that remains of a large Utopian Community"

and he sighed, "not founded in reality." We had finished

lunch, and the Huxleys got up and escorted me down to the

road where we could see twin portals still standing, some

wrecked buildings, and a lot of rusting farm machinery.

Huxley pondered awhile,

and then answered: "They had

about 300 acres, enough capital and enough

equipment and idealists to last up until about 1925.

Then the intense conflict between idealism and actuality

began to cut into their hopes. And so they got to

fighting, and within a few years the whole thing just

fell to bits, and what is left of the wreckage across

the road is all that remains of a large Utopian Community"

and he sighed, "not founded in reality." We had finished

lunch, and the Huxleys got up and escorted me down to the

road where we could see twin portals still standing, some

wrecked buildings, and a lot of rusting farm machinery.

"Well," I said, "they must have gone through a hellish

time before the whole thing went belly up."

"Well," I said, "they must have gone through a hellish

time before the whole thing went belly up."

"No," said Mr. Huxley, reflectively, "if you are thinking

of the Dante-esque hell of The

Divine Comedy, it wasn't like

that. Because Dante being a writer knew that he had to

provide a situation where people could actually

watch the sufferers in hell without themselves being part

of it. But here at Llano, since everyone was involved, there

were no spectators apart. You had to be in it and of

it to experience what they went through. Whereas in

Dante's observation of the Inferno you can have a safe

seat and comment: "Is that Smith down there in the fire

pits? Terrible sight! And a bit of a nasty smell

too ----" Huxley held his hand over his nose and made a

grimace. And then continued: "But however much we feel

for him, it's perhaps best not to be where he is, don't you

think?"

"No," said Mr. Huxley, reflectively, "if you are thinking

of the Dante-esque hell of The

Divine Comedy, it wasn't like

that. Because Dante being a writer knew that he had to

provide a situation where people could actually

watch the sufferers in hell without themselves being part

of it. But here at Llano, since everyone was involved, there

were no spectators apart. You had to be in it and of

it to experience what they went through. Whereas in

Dante's observation of the Inferno you can have a safe

seat and comment: "Is that Smith down there in the fire

pits? Terrible sight! And a bit of a nasty smell

too ----" Huxley held his hand over his nose and made a

grimace. And then continued: "But however much we feel

for him, it's perhaps best not to be where he is, don't you

think?"

After Huxley had spoken about Dante, he

turned to other matters. To hear him take up a theme, develop it, and

then resolve the questions which appeared was really thrilling. He knew

what he was saying and he said what he was knowing. There was a natural

punctuation in his speech, with commas and semicolons placed correctly.

Paragraphs were properly placed too, and the climax or "point" of what

he was saying was never neglected. This speech, or "conversation", as you

will, was wonderful to hear. For I had never heard it done so well. And

it was also a matter of cadence, style, emphasis, supporting points,

and asterisks of intuition. Nothing canned (or rehearsed) about it at all.

And yet, if it was transcribed, it would read as clearly and as well as

it had been heard.

After Huxley had spoken about Dante, he

turned to other matters. To hear him take up a theme, develop it, and

then resolve the questions which appeared was really thrilling. He knew

what he was saying and he said what he was knowing. There was a natural

punctuation in his speech, with commas and semicolons placed correctly.

Paragraphs were properly placed too, and the climax or "point" of what

he was saying was never neglected. This speech, or "conversation", as you

will, was wonderful to hear. For I had never heard it done so well. And

it was also a matter of cadence, style, emphasis, supporting points,

and asterisks of intuition. Nothing canned (or rehearsed) about it at all.

And yet, if it was transcribed, it would read as clearly and as well as

it had been heard.

I knew about Huxley's enthusiasm for Thomas

Love Peacock (1785 - 1866), and I had made it a point (not knowing I was going to meet

him!) to read carefully and with enthusiasm the wonderful comic novels

written by this unusual 19th century author.

I knew about Huxley's enthusiasm for Thomas

Love Peacock (1785 - 1866), and I had made it a point (not knowing I was going to meet

him!) to read carefully and with enthusiasm the wonderful comic novels

written by this unusual 19th century author.

I bring this up because I could sense and feel in the

cadences of Husley's expression, the sure influence of Peacock in the

background. Indeed, before leaving I remarked upon this to him and he waved

me away by saying: "Oh, you are too kind!" But I could tell he was pleased

that I had brought it up.

I bring this up because I could sense and feel in the

cadences of Husley's expression, the sure influence of Peacock in the

background. Indeed, before leaving I remarked upon this to him and he waved

me away by saying: "Oh, you are too kind!" But I could tell he was pleased

that I had brought it up.

And so the Huxleys continued for a while telling me about the

Lost community of Llano, and how it had vanished from the

Mohave Desert in only a few years, like a sodden rainbow

which fell from the sky before it could manifest as

a full spectrum.

And so the Huxleys continued for a while telling me about the

Lost community of Llano, and how it had vanished from the

Mohave Desert in only a few years, like a sodden rainbow

which fell from the sky before it could manifest as

a full spectrum.

And then Huxley, remembering no doubt what Isherwood had

said about me, asked: "What about your tussle with the draft

board about being a conscientious objector?"

And then Huxley, remembering no doubt what Isherwood had

said about me, asked: "What about your tussle with the draft

board about being a conscientious objector?"

I answered that the way things were going, they were

reserving for me a suite in the Graybar Hotel."

I answered that the way things were going, they were

reserving for me a suite in the Graybar Hotel."

"The what?" Huxley asked.

"The what?" Huxley asked.

"Oh," I answered, "it's just a more pleasant term for the

Federal Penitentiary which is more or less set up to

receive rebels who have a cause, even if not guilty of

moral turpitude in its demonstration."

"Oh," I answered, "it's just a more pleasant term for the

Federal Penitentiary which is more or less set up to

receive rebels who have a cause, even if not guilty of

moral turpitude in its demonstration."

Then, Mr. Huxley asked me: "So far in your Hejira in this

war-torn world, have you been threatened with violence?"

Then, Mr. Huxley asked me: "So far in your Hejira in this

war-torn world, have you been threatened with violence?"

"Only once directly," I answered, when I was in a movie

theater, and they were showing footage of a group of

Japanese soldiers being incinerated with a flame thrower.

And the audience was laughing and clapping as if they had

just seen a comedty skit. After which everybody was

supposed to stand up and sing the National Anthem. I

refused to stand up, and came close to getting beaten up at

that time."

"Only once directly," I answered, when I was in a movie

theater, and they were showing footage of a group of

Japanese soldiers being incinerated with a flame thrower.

And the audience was laughing and clapping as if they had

just seen a comedty skit. After which everybody was

supposed to stand up and sing the National Anthem. I

refused to stand up, and came close to getting beaten up at

that time."

Then I remembered something

Krishanji had told me, and I repeated it to them: "He told

me that I did not come from a country with a pacifist

background, like India's, but with a strong violent

history. And that violence was not only a part and parcel

of my background, but was now present in my very blood and

bones. How to transcend that background without getting

crazy in the process?

Then I remembered something

Krishanji had told me, and I repeated it to them: "He told

me that I did not come from a country with a pacifist

background, like India's, but with a strong violent

history. And that violence was not only a part and parcel

of my background, but was now present in my very blood and

bones. How to transcend that background without getting

crazy in the process?

And I also remembered what I had

heard when temporarily

incarcerated in the San Francisco County Jail, before

pre-sentencing review of my case. A middle-aged man,

obviously in bad shape, was unceremoniously brought into

the bullpen and just dumped on the floor, rather than

being led to a cell. After awhile I went over and asked

him where he had come from. "From Alcatraz on a writ of

habeas corpus." I asked "What happens if you get out of

line on Alcatraz?" He answered off-handedly: "Oh, they

take you down to deep-lock (which is the deepest dungeon)

and there they sap the whey out of you!"

And I also remembered what I had

heard when temporarily

incarcerated in the San Francisco County Jail, before

pre-sentencing review of my case. A middle-aged man,

obviously in bad shape, was unceremoniously brought into

the bullpen and just dumped on the floor, rather than

being led to a cell. After awhile I went over and asked

him where he had come from. "From Alcatraz on a writ of

habeas corpus." I asked "What happens if you get out of

line on Alcatraz?" He answered off-handedly: "Oh, they

take you down to deep-lock (which is the deepest dungeon)

and there they sap the whey out of you!"

Mrs. Huxley interrupted to ask:

"What is a sap?" I answered: "A sap is a leather bag,

filled with buckshot. It gives serious pain, but it leaves

no marks, so is used for third-degree interrogations from

which "free and voluntary" confessions are said to come.

Mrs. Huxley interrupted to ask:

"What is a sap?" I answered: "A sap is a leather bag,

filled with buckshot. It gives serious pain, but it leaves

no marks, so is used for third-degree interrogations from

which "free and voluntary" confessions are said to come.

Mr. Huxley interjected: And what

was the County Jail like?"

Mr. Huxley interjected: And what

was the County Jail like?"

"Oh, I answered, it was a place

set up to punish either violence or non-violence, but it

definitely had a tone of anger and fear.

"Oh, I answered, it was a place

set up to punish either violence or non-violence, but it

definitely had a tone of anger and fear.

Huxley asked: "Did you meet any

memorable people? I said, "Yes, one outstanding person,

who had suddenly become a conscientious objector under

exceptional circumstances and was brutally punished for

it.

Huxley asked: "Did you meet any

memorable people? I said, "Yes, one outstanding person,

who had suddenly become a conscientious objector under

exceptional circumstances and was brutally punished for

it.

"Please tell us about him", Huxley

asked. I responded: "This man, called Slim, had been a

military policeman guarding a prison compound. He was an

expert in Judo and a noted marksman. One of his prisoners

escaped. He had raised his rifle, but hesitated to shoot

the running man. One of his superiors called out: "Shoot,

Slim! For God's sake, shoot!" Somehow the suddenness of

the event, combined with the order: "For God's sake,

shoot!" completely baffled him, and he threw down his

rifle. A serious situation. Because he was then given the

5-year sentence of the escaped prisoner. And that was

five years at hard labor. Which meant that he was taken to

a local disciplinary camp. Under armed guard, he was

ordered to labor in a swamp, carrying stones. If he did

not carry or arrange the stones quickly enough, the guard

would beat him strongly with a sharp bamboo switch. After

a few weeks of this 'drill' he wondered how long he could

take it. Then suddenly he had a plan, and put it into

effect. The guard had beaten him with the bamboo with

particular ferocity. But he was able to grab the bamboo

and pull the guard into the pit. There he was able to

break his shoulder, grab his gun and get out of the pit,

where he commandeered a boat and escaped from the scene.

But then, aware of the grave future trouble he was causing

himself, he turned himself in, and was then awaiting trial

in the County Jail where, because they had failed to

search him, he came into the jail with a large .45 Colt

Pistol on a thong in his jacket. Later he called for the

FBI to come visit him. When the two men walked into his

cell, much to their fear and astonishment he pulled out

the .45 and handed it to them. I never knew what happened

to Slim. because I was myself temporarily released a few

days later. "So," Mr. Huxley concluded, "in a violent

country Slim refuses to kill in a crisis, is then treated

harshly, escapes and faces a dark future."

"Please tell us about him", Huxley

asked. I responded: "This man, called Slim, had been a

military policeman guarding a prison compound. He was an

expert in Judo and a noted marksman. One of his prisoners

escaped. He had raised his rifle, but hesitated to shoot

the running man. One of his superiors called out: "Shoot,

Slim! For God's sake, shoot!" Somehow the suddenness of

the event, combined with the order: "For God's sake,

shoot!" completely baffled him, and he threw down his

rifle. A serious situation. Because he was then given the

5-year sentence of the escaped prisoner. And that was

five years at hard labor. Which meant that he was taken to

a local disciplinary camp. Under armed guard, he was

ordered to labor in a swamp, carrying stones. If he did

not carry or arrange the stones quickly enough, the guard

would beat him strongly with a sharp bamboo switch. After

a few weeks of this 'drill' he wondered how long he could

take it. Then suddenly he had a plan, and put it into

effect. The guard had beaten him with the bamboo with

particular ferocity. But he was able to grab the bamboo

and pull the guard into the pit. There he was able to

break his shoulder, grab his gun and get out of the pit,

where he commandeered a boat and escaped from the scene.

But then, aware of the grave future trouble he was causing

himself, he turned himself in, and was then awaiting trial

in the County Jail where, because they had failed to

search him, he came into the jail with a large .45 Colt

Pistol on a thong in his jacket. Later he called for the

FBI to come visit him. When the two men walked into his

cell, much to their fear and astonishment he pulled out

the .45 and handed it to them. I never knew what happened

to Slim. because I was myself temporarily released a few

days later. "So," Mr. Huxley concluded, "in a violent

country Slim refuses to kill in a crisis, is then treated

harshly, escapes and faces a dark future."

I then asked one more question of

Mr. Huxley: "Do you think in this world there will ever

be a true culture of ends and means governing life?"

I then asked one more question of

Mr. Huxley: "Do you think in this world there will ever

be a true culture of ends and means governing life?"

He paused for a moment before

replying:

"Unfortunately, the possibility is minute! But this

doesn't mean that we should give up or that the game is not

worth the candle -- especially if the candle is lit with

the living flame of love!"

He paused for a moment before

replying:

"Unfortunately, the possibility is minute! But this

doesn't mean that we should give up or that the game is not

worth the candle -- especially if the candle is lit with

the living flame of love!"

I thanked the Huxleys for their

gracious hospitality and was about to leave when Huxley put

up his hand and said: "One favor from you, please: If you

are put in prison, please send me a letter, and I will

surely reply."

I thanked the Huxleys for their

gracious hospitality and was about to leave when Huxley put

up his hand and said: "One favor from you, please: If you

are put in prison, please send me a letter, and I will

surely reply."

I thanked him again before

leaving. And I did send him a letter from prison, and he

did graciously reply.

I thanked him again before

leaving. And I did send him a letter from prison, and he

did graciously reply.

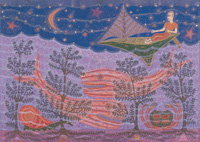

And two years

later I was able to read his splendid

Perennial

Philosophy, and then realized that, at the time of my

visit, he was just putting the finishing touches on it.

In it, I

discovered the quote from the 10th-Century Egyptian Sufi

Saint, Mohammed Al-Niffari, which directly inspired me to

paint The Voyage.

And two years

later I was able to read his splendid

Perennial

Philosophy, and then realized that, at the time of my

visit, he was just putting the finishing touches on it.

In it, I

discovered the quote from the 10th-Century Egyptian Sufi

Saint, Mohammed Al-Niffari, which directly inspired me to

paint The Voyage.

Back to the home page

of The Voyage